A Study of Dispensationalism

by A.W. Pink

Chapter 2

Some Dispensationalists do not go quite so far as others in arbitrarily erecting notice-boards over large sections of Scripture, warning Christians not to tread on ground which belongs to others, yet there is general agreement among them that the Gospel of Matthew—though it stands at the beginning of the New Testament and not at the close of the Old!—pertains not to those who are members of the mystical body of Christ, but is “entirely Jewish,” that the sermon on the mount is “legalistic” and not evangelistic, and that its searching and flesh-withering precepts are not binding upon Christians. Some go so far as to insist that the great commission with which it closes is not designed for us today, but is meant for “a godly Jewish remnant” after the present era is ended. In support of this wild and wicked theory, appeal is made to and great stress laid upon the fact that Christ is represented, most prominently, as “the son of David” or King of the Jews; but they ignore another conspicuous fact, namely that in its opening verse the Lord Jesus is set forth as “the son of Abraham,” and he was a Gentile! What is still more against this untenable hypothesis—and as though the Holy Spirit designedly anticipated and refuted it—is the fact that Matthew’s is the only one of the four Gospels where the Church is actually mentioned twice (16:18; 18:17)!—though in John’s Gospel its members are portrayed as branches of the Vine, members of Christ’s flock, which are designations of saints which have no dispensational limitations.

Equally remarkable is the fact that the very same Epistle which contains the verse (2 Tim. 2:15) on which this modern system is based emphatically declares: “All Scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness; that the man of God may be perfect, thoroughly furnished unto all good works” (3:16,17). So far from large sections of Scripture being designed for other companies, and excluded from our immediate use, ALL Scripture is meant for and is needed by us. First, all of it is “profitable for doctrine,” which could not be the case if it were true (as Dispensationalists dogmatically insist) that God has entirely different methods of dealing with men in past and future ages from the present one. Second, all Scripture is given us “for instruction in righteousness” or right doing, but we are at a complete loss to know how to regulate our conduct if the precepts in one part of the Bible are now outdated (as the teachers of error assert) and injunctions of a contrary character have displaced them; and if certain statutes are meant for others who will occupy this scene after the Church has been removed from it. Third, all Scripture is given that a man of God might be “perfect, thoroughly furnished unto all good works”—every part of the Word is required in order to supply him with all needed instructions and to produce a full-orbed life of godliness.

When the Dispensationalist is hard pressed with those objections, he endeavors to wriggle out of his dilemma by declaring that though all Scripture be for us much of it is not addressed to us. But really, that is a distinction without a difference. In his exposition of Hebrews 3:7-11, Owen rightly pointed out that when making quotation from the Old Testament the Apostle prefaced it with “the Holy Spirit saith” (not “said”), and remarked, “Whatever was given by inspiration from the Holy Spirit and is recorded in the Scriptures for the use of the Church, He contrived to speak it to us unto this day. As He liveth for ever so He continues to speak for ever; that is, whilst His voice or word shall be of use for the Church—He speaks now unto us . . . .Many men have invented several ways to lessen the authority of the Scriptures, and few are willing to acknowledge an immediate speaking of God unto them therein.” To the same effect wrote that sound commentator Thomas Scott, “Because of the immense advantages of perseverance, and the tremendous consequences of apostasy, we should consider the words of the Holy Spirit as addressed to us.”

Not only is the assertion that though all Scripture be for us all is not to us meaningless, but it is also impertinent and impudent, for there is nothing whatever in the Word of Truth to support and substantiate it. Nowhere has the Spirit given the slightest warning that such a passage is “not to the Christian,” and still less that whole books belong to someone else. Moreover, such a principle is manifestly dishonest. What right have I to make any use of that which is the property of another? What would my neighbor think were I to take letters which were addressed to him and argue that they were meant for me? Furthermore, such a theory, when put to the test, is found to be unworkable. For example, to whom is the book of Proverbs addressed, or for that matter, the first Epistle of John? Personally, this writer, after having wasted much time in perusing scores of books which pretended to rightly divide the Word, still regards the whole of Scripture as God’s gracious revelation to him and for him, as though there were not another person on earth, conscious that he cannot afford to dispense with any portion of it; and he is heartily sorry for those who lack such a faith. Pertinent in this connection is that warning, “But fear, lest by any means, as the serpent beguiled Eve . . . so your minds should be corrupted from the simplicity that is in Christ” (2 Cor. 11:3).

But are there not many passages in the Old Testament which have no direct bearing upon the Church today? Certainly not. In view of 1 Corinthians 10:11—”Now all these things happened unto them for ensamples [margin, “types”]: and they are written for our admonition”—Owen pithily remarked: “Old Testament examples are New Testament instructions.” By their histories we are taught what to avoid and what to emulate. That is the principal reason why they are recorded: that which hindered or encouraged the Old Testament saints was chronicled for our benefit. But, more specifically, are not Christians unwarranted in applying to themselves many promises given to Israel according to the flesh during the Mosaic economy, and expecting a fulfillment of the same unto themselves? No indeed, for if that were the case, then it would not be true that “whatsoever things were written aforetime were written for our learning, that we through patience and comfort of the scriptures might have hope” (Rom. 15:4). What comfort can I derive from those sections of God’s Word which these people say “do not belong to me”? What “hope” (i.e. a well-grounded assurance of some future good) could possibly be inspired today in Christians by what pertains to none but Jews? Christ came here, my reader, not to cancel, but “to confirm the promises made unto the fathers: and that the Gentiles might glorify God for His mercy” (Rom. 15:8,9)!

It must also be borne in mind that, in keeping with the character of the covenant under which they were made, many of the precepts and the promises given unto the patriarchs and their descendants possessed a spiritual and typical significance and value, as well as a carnal and literal one. As an example of the former, take Deuteronomy 25:4, “Thou shalt not muzzle the ox when he treadeth out the corn,” and then mark the application made of those words in 1 Corinthians 9:9,10: “Doth God take care for oxen? Or saith He it altogether for our sakes? For our sakes, no doubt, this is written: that he that ploweth should plow in hope.” The word “altogether” is probably a little too strong here, for pantos is rendered “no doubt” in Acts 28:4, and “surely” in Luke 4:23, and in the text signifies “assuredly” (Amer. RV) or “mainly for our sakes.” Deuteronomy 25:4 was designed to enforce the principle that labour should have its reward, so that men might work cheerfully. The precept enjoined equity and kindness: if so to beasts, much more so to men, and especially the ministers of the Gospel. It is a striking illustration of the freedom with which the Spirit of grace applies the Old Testament Scriptures, as a constituent part of the Word of Christ, unto Christians and their concerns.

What is true of the Old Testament precepts (generally speaking, for there are, of course, exceptions to every rule) holds equally good to the Old Testament promises—believers today are fully warranted in mixing faith therewith and expecting to receive the substance of them. First, because those promises were made to saints as such, and what God gives to one He gives to all (2 Pet. 1:4)—Christ purchased the self-same blessings for every one of His redeemed. Second, because most of the Old Testament promises were typical in their nature: earthly blessings adumbrated heavenly ones. That is no arbitrary assertion of ours, for anyone who has been taught of God knows that almost everything during the old economies had a figurative meaning, shadowing forth the better things to come. Many proofs of this will be given by us a little later. Third, a literal fulfillment to us of those promises must not be excluded, for since we be still on earth and in the body our temporal needs are the same as theirs, and if we meet the conditions attached to those promises (either expressed or implied), then we may count upon the fulfillment of them: according unto our faith and obedience so will it be unto us.

But surely we must draw a definite and broad line between the Law and the Gospel. It is at this point that the Dispensationalist considers his position to be the strongest and most unassailable; yet nowhere else does he more display his ignorance, for he neither recognizes the grace of God abounding during the Mosaic era, nor can he see that Law has any rightful place in this Christian age. Law and grace are to him antagonistic elements, and (to quote one of his favorite slogans) “will no more mix than will oil and water.” Not a few of those who are now regarded as the champions of orthodoxy tell their hearers that the principles of law and grace are such contrary elements that where the one be in exercise the other must necessarily be excluded. But this is a very serious error. How could the Law of God and the Gospel of the grace of God conflict? The one exhibits Him as “light,” the other manifest Him as “love” (1 John 1:5; 4:8), and both are necessary in order fully to reveal His perfections: if either one be omitted only a one-sided concept of His character will be formed. The one makes known His righteousness, the other displays His mercy, and His wisdom has shown the perfect consistency there is between them.

Instead of law and grace being contradictory, they are complementary. Both of them appeared in Eden before the Fall. What was it but grace which made a grant unto our first parents: “Of every tree of the garden thou mayest freely eat”? And it was law which said, “But of the tree of knowledge of good and evil, thou shalt not eat of it.” Both of them are seen at the time of the great deluge, for we are told that “Noah found grace in the eyes of the Lord” (Gen. 6:8), as His subsequent dealings with him clearly demonstrated; while His righteousness brought in a flood upon the world of the ungodly. Both of them operated side by side at Sinai, for while the majesty and righteousness of Jehovah were expressed in the Decalogue, His mercy and grace were plainly evinced in the provisions He made in the whole Levitical system (with its priesthood and sacrifices) for the putting away of their sins. Both shone forth in their meridian glory at Calvary, for whereas on the one hand the abounding grace of God appeared in giving His own dear Son to be the Saviour of sinners, His justice called for the curse of the Law to be inflicted upon Him while bearing their guilt.

In all of God’s works and ways we may discern a meeting together of seemingly conflicting elements—the centrifugal and the centripetal forces which are ever at work in the material realm illustrate this principle. So it is in connection with the operations of Divine providence: there is a constant interpenetrating of the natural and supernatural. So too in the giving of the sacred Scriptures: they are the product both of God’s and man’s agency: they are a Divine revelation, yet couched in human language, and communicated through human media; they are inerrantly true, yet written by fallible men. They are Divinely inspired in every jot and tittle, yet the superintending control of the Spirit over the penmen did not exclude nor interfere with the natural exercise of their faculties. Thus it is also in all of God’s dealings with mankind: though He exercises His high sovereignty, yet He treats with them as responsible creatures, putting forth His invincible power upon and within them, but in no wise destroying their moral agency. These may present deep and insoluble mysteries to the finite mind, nevertheless they are actual facts.

In what has just been pointed out—to which other examples might be added (the person of Christ, for instance, with His two distinct yet conjoined natures, so that though He was omniscient yet He “grew in wisdom”; was omnipotent, yet wearied and slept; was eternal, yet died)—why should so many stumble at the phenomenon of Divine law and Divine grace being in exercise side by side, operating at the same season? Do law and grace present any greater contrast than the fathomless love of God unto His children, and His everlasting wrath upon His enemies? No indeed, not so great. Grace must not be regarded as an attribute of God which eclipses all His other perfections. As Romans 5:21 so plainly tells us, “That as sin hath reigned unto death, even so might grace reign through righteousness,” and not at the expense of or to the exclusion of it. Divine grace and Divine righteousness, Divine love and Divine holiness, are as inseparable as light and heat from the sun. In bestowing grace, God never rescinds His claims upon us, but rather enables us to meet them. Was the prodigal son, after his penitential return and forgiveness, less obliged to conform to the laws of his Father’s house than before he left it? No indeed, but more so.

That there is no conflict between the Law and the Gospel of the grace of God is plain enough in Romans 3:31: “Do we then make void the law through faith? God forbid: yea, we establish the law.” Here the Apostle anticipates an objection which was likely to be brought against what he said in verses 26-30. Does not the teaching that justification is entirely by grace through faith evince that God has relaxed His claims, changed the standard of His requirements, set aside the demands of His government? Very far from it. The Divine plan of redemption is in no way an annulling of the Law, but rather the honoring and enforcing of it. No greater respect could have been shown to the Law than in God’s determining to save His people from its course by sending His co-equal Son to fulfill all its requirements and Himself endure its penalty. Oh, marvel of marvels; the great Legislator humbled Himself unto entire obedience to the precepts of the Decalogue. The very One who gave the Law became incarnate, bled and died, under its condemning sentence, rather than that a tittle thereof should fail. Magnified thus was the Law indeed, and for ever “made honorable.”

God’s method of salvation by grace has “established the law” in a threefold way. First, by Christ, the Surety of God’s elect, being “made under the law” (Gal. 4:4), fulfilling its precepts (Matt. 5:17), suffering its penalty in the stead of His people, and thereby He has “brought everlasting righteousness” (Dan. 9:24). Second, by the Holy Spirit, for at regeneration He writes the Law on their hearts (Heb. 8:10), drawing out their affections unto it, so that they “delight in the law of God after the inward man” (Rom. 7:22). Third, as the fruit of his new nature, the Christian voluntarily and gladly takes the Law for his rule of life, so that he declares, “with the mind I myself serve the law” (Rom. 7:25). Thus is the Law “established” not only in the high court of heaven, but in the souls of the redeemed. So far from law and grace being enemies, they are mutual handmaids: the former reveals the sinner’s need, the latter supplies it; the one makes known God’s requirements, the other enables us to meet them. Faith is not opposed to good works, but performs them in obedience to God out of love and gratitude.

Biblical Definition of Spiritual Abuse

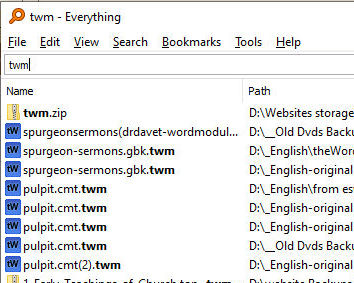

Biblical Definition of Spiritual Abuse Helpful Windows User Tip for "Searching Everything" on your PC.

Helpful Windows User Tip for "Searching Everything" on your PC.